Hard Land

Maybe I’m soft, but so are the leaves crumbling to ash on the forest floor, the petals of wildflowers hungry for the sun, and the sky when dusk lights the firmament on fire.

[Originally published in November 2014)

Within the boundaries of the Chippewa National Forest, Minnesota, there is a triangle of land, 13 acres total, bound on each side by a highway, a dirt road, and a primitive trail. It’s a wild tangle of aspens, pines, and birch, carpeted in the warmer months by the corpses of maple leaves past, if not by water and marsh-grass and mud. A modular home sits along the driveway, just off the dirt road, on the only patch of land that remains cleared. This is the place that has been the epicenter of my family’s being for three generations, and hopefully many more.

Even when we did not own this place, the land was ours. We spent decades out on the lakes in quiet contemplation, building up the property under the heat of hot summer suns, drinking Grain Belt and Miller after the stars crept into the sky. Fifteen years ago, we officially bought the place, after renting it, or places nearby, for almost fifty, and my grandparents retired there, rooting themselves to that plot, making this place ours forever.

My Darwin and Marian Mithun wanted solitude, a place could get away from the demands of the nine-to-five for a few days to rest. They were not ones to call in sick, not when livestock needed to be tended or unions needed to be organized. They taught their sons the lesson that there was no substitute for hard work, that calloused hands were the only hands worth having. They needed this excuse to leave their hard ethic behind. They would have otherwise died decades ago.

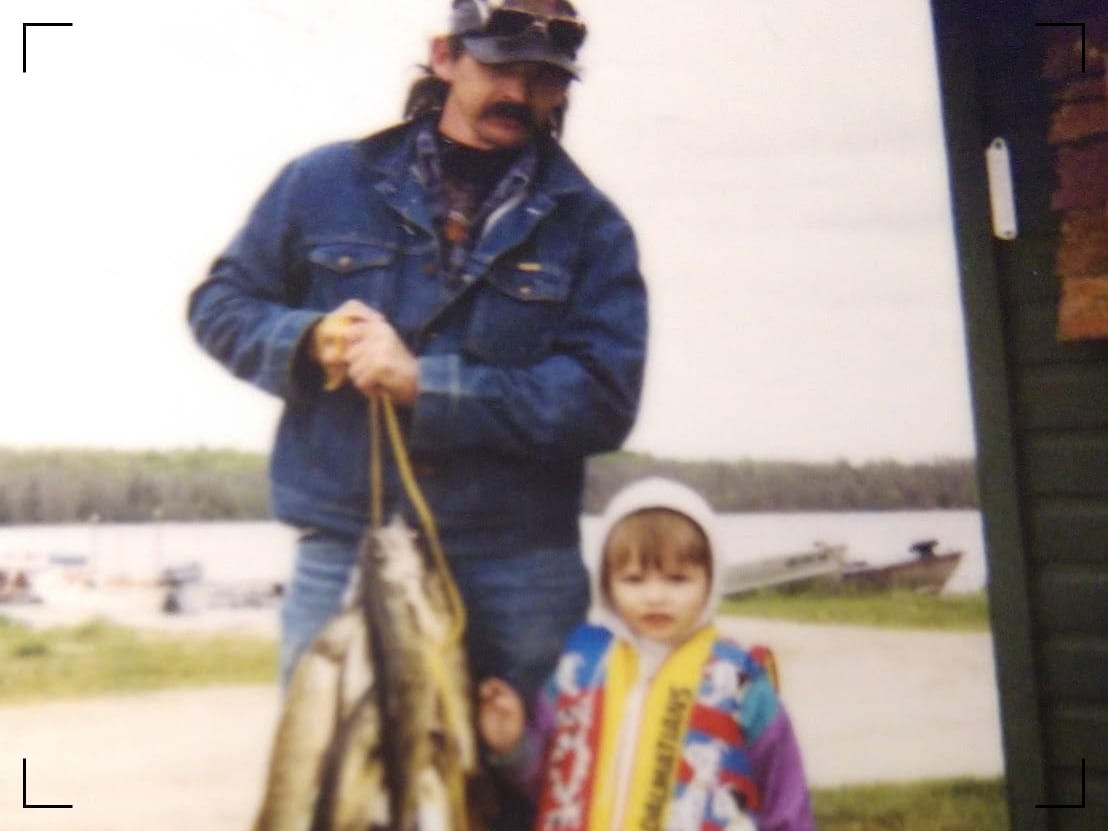

My father and my uncle rebelled against this attitude in their youth. The both of them saw the forest as a playground, rather than a rest home. My father often recalls the hunts of the seventies and eighties, the drunken deer camps and the wild nights out at Cannibal Junction, a dive bar at the crossroads of Highway 6 and County Road 35, where he with his brother and their biker gangs brought music to the woods, interrupting the symphonies of crickets and owls with good hard rock and roll. Naturally, my grandparents disapproved. My father, in particular, felt his father’s disdain, punching a rift between the two of them that had never been repaired.

I was born as the last echoes of those wild days faded from the empty spaces between the trees. When I was two, my grandmother and I planted a tree behind the house. I felt the cold, hard dirt of this land between my fingers for the first time that day as I rolled it into a mound around that tiny stem of pine. It stands forty-four feet tall now, sticking out above the slow growth trees placed around it.

I stick out in this family too, by virtue of my Pennsylvanian mother. She visited the woods once, when I was a baby in her arms, and never returned. I asked her why when I was four, when I realized that she never accompanied me and my father on our trips. She thought about it long enough to take a drag of her cigarette, then, flicking her ashes into the kitchen sink, replied, “I’m too soft for a place like that.”

My mother was never a soft woman. I knew that even then. Her answer was something that I often thought about, but didn’t understand until a combination of time, maturity, and distance lifted the fog from those marshes and allowed me to see into the heart of that forest, into the heart of my own family.

There is never true silence in those woods. Even when you quiet yourself, stopping your breathing, tuning out the thud of your own heart, there is always the noise in the background, whether it's the chirping of frogs and insects or the rattling of leaves in the wind. Even in the winter, when the cold drives nearly every animal to sleep, you can hear the call of wolves racing across the snow or the occasional snap of the branches under the weight of the ice.

There is never true silence in this family. Even when we put on our stone masks and deny that we have problems, that we drink too much and share too little, those issues still float about in the aether. Our problems pervade every interaction between us, no matter how much we steel our resolve against them. We make islands of ourselves, but we can never escape the sight of another’s shore.

It was on the night of my grandfather’s wake, when the entire family gathered for the funeral at the house, that I, drunken and sobbing, walked out into the woods and tossed aside my stone mask. After the visitation, we made our procession from the funeral home right to the corner back table of the Deer River American Legion, ostensibly to buy some flags to honor my grandfather’s memory, though all of us old enough to drink somehow found full glasses in front of us. I don’t remember how I got home. One moment, I was at the bar, dabbing at a spot of whiskey on my dress, and the next I was sitting at my grandmother’s kitchen table, staring at the empty spot across from me where my grandfather used to sit. My family spoke around me. After the darkness of that day, nothing they said seemed to matter.

My grandfather’s ashes sat in a box on top of the washing machine, out of the room, forgotten already, while his wife and sons talked about the fishing report between sips of beer. I thought we should talk about him, not about the water quality in Jesse Lake. We were going to bury him the next day; I thought we should spend time with him, at least keeping his remains in the same room with us. I tried to bottle the distress up. This is their process, I told myself. It’s hard. They don’t want to think about him. It hurts.

The problem I have with alcohol is that you can’t get me to shut up once I’ve had a few, and after I’ve had more than a few, I can be savage. I took a deep breath, unable to hold it in any longer. I started to scream. I started to cry. I told them all to get over themselves, to stop acting as if nothing had happened, as if they hadn’t felt the agony of my grandfather’s last years alongside him, and as if his death was just one among the many thousands of people who passed on that May 19th. I told them all that they were petty, that they couldn’t drop their baggage at the door for one week and be honest with one another about their feelings, for grandpa’s sake. My father’s girlfriend told me to stop being so damn soft. I told her to screw off, and, noticing my father’s silence, another link in a chain of years of indecisiveness when it came to me, I slipped on shoes and walked out, following the trail, not stopping until I reached the deer-camp in the center of our woods. I climbed halfway up the rickety stairs of our permanent stand, sat, and put my head in my hands.

I couldn’t sit for a moment longer in that cold house with its hard people, saying little and staring at nothing. My retreat into isolation was out of want to be closer to something alive. This forest is not my playground; it is not my rest home. It isn’t mine at all, as no one in my family thinks me fit to claim it, but nonetheless it is there to hold me when I need it, cloaking me in darkness, giving me that moment alone that I so desperately needed. Maybe I’m soft, but so are the leaves crumbling to ash on the forest floor, the petals of wildflowers hungry for the sun, and the sky when dusk lights the firmament on fire. It is a land of hard people, but it is not hard land.